Commande du festival Aspects 2024

Instrumentation: viola and cello duo

Duration: c. 20’

First performance: 24 March 2024, by students of Conservatoire & Orchestre de Caen, France

Chanson à Cordes is a collection of 8 duos based on traditional songs from the Normandy region of France as collected in the online resource base du patrimoine oral de Normandie (http://normandie.patrimoine-oral.org). They cover the familiar topics of folk music: love, loss, nature and the supernatural. They can be played individually or as a set, and are a response to an invitation from the Conservatoire de Caen to write string duos accessible to students at the conservatoire.

These duos extend the principles of my earlier collection Òran Fìdhle / Violin Song (2021-22), derived from traditional Gaelic song, which itself followed the model of Bartók’s 44 Duos for 2 Violins (1931). To an even greater extent than Òran Fìdhle, with Chanson à Cordes I must acknowledge a distance from the source material, geographically and musically. Although as a teenager I was an active performer of folk and related musics, this was in the Scottish / Celtic traditions, not those of France. The commission from the Conservatoire de Caen offered me an ideal opportunity to immerse myself for a time in the folk music of a different, though related, culture.

Nevertheless, because it is not ‘my’ music, I want to make the distance clear: these are not arrangements or recreations such as a folk musician might legitimately make, but rather new pieces of ‘contemporary classical’ music written by way of the Normandy originals. These duos are therefore resolutely not folk music, even though they come from folk music. A double translation takes place: from vocal to instrumental music and from work-song to concert-piece. My approach to respecting the integrity of the source is to harness the difference that these translations necessarily entail: freedoms (and expectations) in timbre and harmony and structure that aren’t necessarily available in the home tradition. It is therefore important that my duos amplify their source rather than erase it, and so each piece has the URL of its audio in the base du patrimoine de Normandie archive printed alongside. Although these are traditional songs, the starting point for my compositions are the specific performances by the specific people acknowledged on each page.

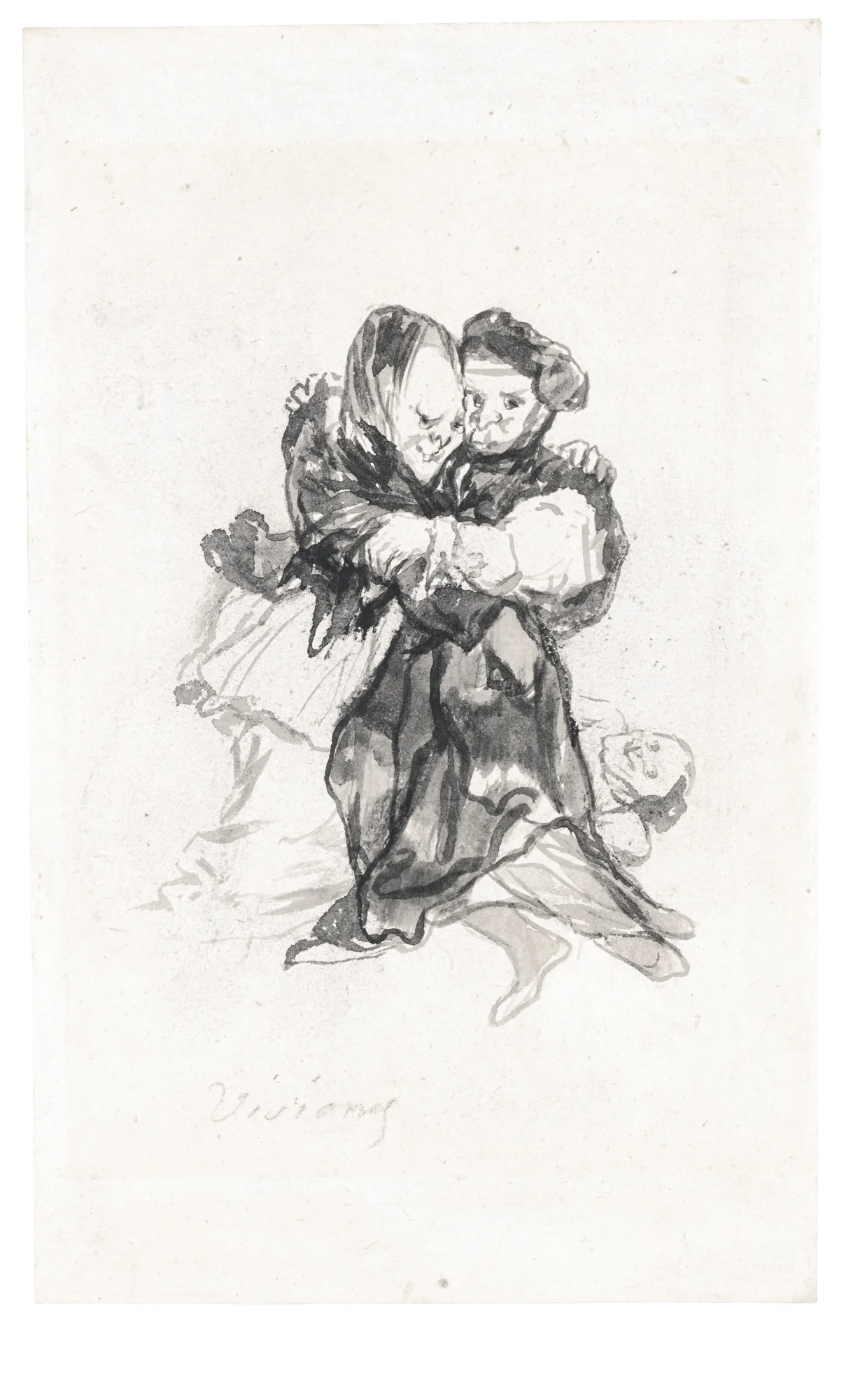

Photo by Gautier Salles on Unsplash